>>> Click here to access this episode of the Syllab Podcast on Spotify <<<

a) Balance of payments

We are now well and truly in the final laps and will devote this chapter to a last organism, not the most complex but arguably one of the most important in our ecosystem: countries. This is not the website or podcast for politics, though I am always happy to share my opinion on ethics when I think there is little by way of subjectivity in my point of view, so the focus here will be a continuation of the previous Chapter 8 on money and banking, thus remaining firmly about the economics. Try as one regime might, there is no escaping the downward pull of government debt, unbalanced budgets or raging inflation and a country or state is truly like a biological being having to maintain homeostasis or head towards its downfall.

Since we have already spent some time describing major international flows of commodities, supply chains and manufacturing dynamics in Chapter 7, we will follow this lead and start with the economic relationship between a country and other countries, which primarily consists of foreign investment and trade. The difference between exports (trade outflows) and imports (trade inflows) is called the balance of trade and a deficit can mean one of three things, or a mix of those: #1 a lack of economic competitivity, #2 a significant dependence on raw materials and commodities due to a lack of natural resources compared to the size of the economy, or #3 the absence of an adequate manufacturing base. The converse is true and a balance of trade surplus tends to be the mark of a competitive economy or one that is relatively small but with a high export level of natural resources. The balance of trade is complemented by the factor income, being the difference between the incoming and outgoing earnings related to foreign direct investments (FDIs), to make up the current account.

On the capital side, FDIs are positive when a country sells an asset to shareholders in a foreign country or when it attracts overseas investments to build new assets. It is generally the mark of a competitive economy whereas a negative FDI balance is typically a sign of offshoring towards more competitive regions. Competitiveness is a function not only of productivity in terms of output units per hour but also of cost; in other words, it is about where the highest value creation takes place – for shareholders that is – and it will vary depending on the manpower intensity of a particular manufacturing process or the nature of the service being performed. There are also other aspects of capital flows such as portfolio investment, international loans or the operations of a central bank but, even if they are included in the capital account computation and are therefore an integral part of the equation in terms of the appreciation or depreciation of the sovereign currency, they tend to be more short-term in nature and may not reflect long-term, structural trends of the economy as a whole. I include a link to the Wikipedia entry for capital account if you wish to read more about this subject.

When summing up the current account and the capital account (sometimes also called the capital and financial account), we obtain the balance of payments. A persistently negative balance of payment reflects an ongoing flow of currency outside the country, meaning there is less demand for the national currency and it will tend to depreciate compared to other currencies, all else being equal, which would lower the onshore cost base and make exports more competitive and imports less so. So, in theory, there exists a natural balancing mechanism, but it generally turns out to be more complex than this because the value of the currency is seldom left to fluctuate without intervention. We’ll cover this in the next section.

The other major way to try and address a structural deficit of the balance of payment is by artificially making imports more expensive in order to try to protect and promote the onshore manufacturing base. If Country A imposes tariffs, which is a tax the importers of Country A and therefore ultimately its consumers will have to pay on imported goods, this will benefit producers based in Country A for that market and it may attract FDIs into the country because, even though the cost base might be more expensive, it allows for the bypassing of the tariffs. Obviously, there is no free lunch and countries with significant exports to Country A that now face tariffs will tend to retaliate both as a way to bargain and to protect their own economy. This is why the lowering of tariffs tends to be coordinated internationally and why an uncoordinated rise can take place very suddenly across the globe. And this tit for tat strategy is entirely predictable because it often happens to be optimal in game theory, from the perspective of each player even if it is far from the best outcome when considering the aggregate result.

b) Monetary policy

The role of monetary policy is to further the growth and economic health of the country through the use of money and other financial levers. One of these is naturally to reach a high level of employment and this is best done by lowering the cost of money, through the central bank’s reference interest rate, so that it becomes easier for companies to borrow and invest into new producing assets for which people will need to be hired. The problem is that, unfortunately, when employment levels fall too low, this puts upward pressure on wages and therefore on the cost of producing goods with companies having no choice but to raise consumer prices to maintain their profit margins. This results in inflation, defined as the average increase of the price of services and goods sold within a given territory.

Inflation is problematic in two major ways. The first is that it erodes the purchasing power of consumers as well as the value of their savings because the same amount of money now buys them less goods. The second is the pressure it applies on the currency to depreciate in relation with other currencies. To understand why, imagine Currency A can be exchanged for Currency B in a 2:1 ratio, meaning I get two units of currency B for every one unit of currency A. Currency A has been experiencing significant inflation, totalling 15% in the last two years so, if the exchange rate has not moved, then the cost of producing goods in Country A has increased by 15% compared to Country B while the exports from Country B into Country A are now 15% cheaper. This of course assumes there was no inflation in Country B so let us assume more realistically that the 15% represents the differential in inflation rather than the absolute level. To avoid losing out economically, Country A should let its currency depreciate so that its exports remain competitive and its current account deficit doesn’t balloon in the red. By how much does the currency need to depreciate? There is no exact theoretical level but the objective should be to allow the economy to regain some competitiveness.

Consequently, central banks tend to be very focused on the inflation rate and manage their monetary policy with a specific target range in mind, or if they are very “open economies” with substantial trade flows, they may seek to control inflation and the country’s competitiveness through the management of their currency’s exchange rate.

On this basis, central banks will consider intervening in the market to buy or sell the currency to prevent or accelerate its depreciation or appreciation and they may lower or raise the reference interest rate. We have seen earlier the consequences of lowering interest rate in terms of employment and possible inflation. When raising interest rate, the effect will be the opposite: it will make borrowing money more expensive and incentivize consumers to save rather than spend because they get better returns on their bank deposit, and this will cool the economy down, hoping not to tilt it into a recession, a situation in which companies hold back on future investments and unemployment surges.

Let us return for a moment to the levers at the disposal of a central bank for stimulating the economy and bring down the level of unemployment. One alternative, and this is the prerogative of the government rather than the central bank, is to carry out large public investments such as building large dams for hydropower, highways and high-speed train tracks. This not only generates employment but it also improves the country’s infrastructure and can have long-term payoffs if done properly, i.e. where there is an actual need for these assets and their construction cost remains reasonable. The other alternative is for the central bank to increase the supply of money; you may recall from S6 Section 8.b that in most countries it is the central bank which distributes newly minted money and it is this institution that decides whether or not to increase the money supply into the economy. Broadly, the increase in the monetary mass ensures there is adequate liquidity in the system, a necessary condition for economic growth. However it can also lead to inflation and therefore the debasing of the currency – this is one of the accusations levelled at fiat currencies and in favour of private currencies with contractual limited issuance although, as I have mentioned in S6 Section 8.f, this is a very weak argument since there is no control on the number of different private currency issuers. Fortunately, at least in theory, the central bank can also remove some liquidity from the financial markets and the economy at large to try to get a handle on inflation. It is a delicate balancing act because actors in the financial markets tend to overreact, both ways. I include a link to the Wikipedia entry for money supply in the last section; note that this is an interesting topic that can get quite technical.

Lastly, and this was alluded to twice before in this chapter, the central bank can support the currency by using its foreign exchange reserves to purchase its own currency in the market, thus countering the volume of sellers. The foreign exchange reserves are an outcome of a positive balance of payment and large reserves provide a strong position from which to fend off market pressure on the currency. Conversely, a very low level of reserves makes it difficult to mitigate the selling pressure and may in fact invite speculators to take a short position, thereby accentuating the pressure. In this case, the central bank may have no choice but to increase interests rate so as to make it attractive for foreign investors to purchase local obligations such as sovereign bonds, thus bringing in capital into the country at the expense of the short-term economic growth.

c) Sovereign debt

Just like a company, a government needs to balance its accounts otherwise it incurs losses and needs to borrow money from various sources to plug the gap, whether financial investors or individual investors, be it domestically or internationally. When the revenues outweigh the expenses, the government budget realizes a primary surplus, and the opposite is called a primary deficit.

Primary implies not final because a government may be saddled with an existing level of debt that it needs to service so that, even if it is able to refinance maturing debt with new one, it still needs to pay interest on the sovereign debt. Paying 3% of interest on 20% debt level is one thing, but servicing interests of 5% on 110% debt level for instance is altogether more challenging. What is the meaning of debt level here? Generally, it is expressed as a percentage of the gross domestic product (GDP), which corresponds to the value of the goods and services produced within the country based on their market price. So in the first example the interest service would be equivalent to 0.6% of GDP and in the second example it would be 5.5% of GDP. How should we think about such levels?

Ideally we would want to have a sense of the debt level as a percentage of the total economy as well as the government’s capacity to service the debt so that a debt to budget percentage might be useful. This may be computed indirectly if we know the budget size as a percentage of the GDP. If it is 40% then the 0.6% becomes effectively a 1.5% budget deficit, calculated as 0.6% divided by 40% and 5.5% would become a 13.75% budget deficit, quite a challenge to balance going forward and therefore this may lead to a runaway indebtedness level. There are two sides in a budget, the expenses and the revenues, and in the case of the government the revenues mostly come from taxes so a level of 40% suggests a wide tax base combined with a high collection rate on taxes owed. In many countries, only one of those variables may be present, or none, in which case the government budget is only a small fraction of the economy, maybe 20% or less and so a 50% debt to GDP level in the latter case is a lot more challenging to service in a country with a budget equal to 20% of the GDP compared to one where it represents 40% of GDP. For context, based on the IMF statistics at end 2023, the level in the USA is about 37%, in Japan around 41%, in France 57%, in India 29%, in Costa Rica 18% and in Ethiopia 11%.

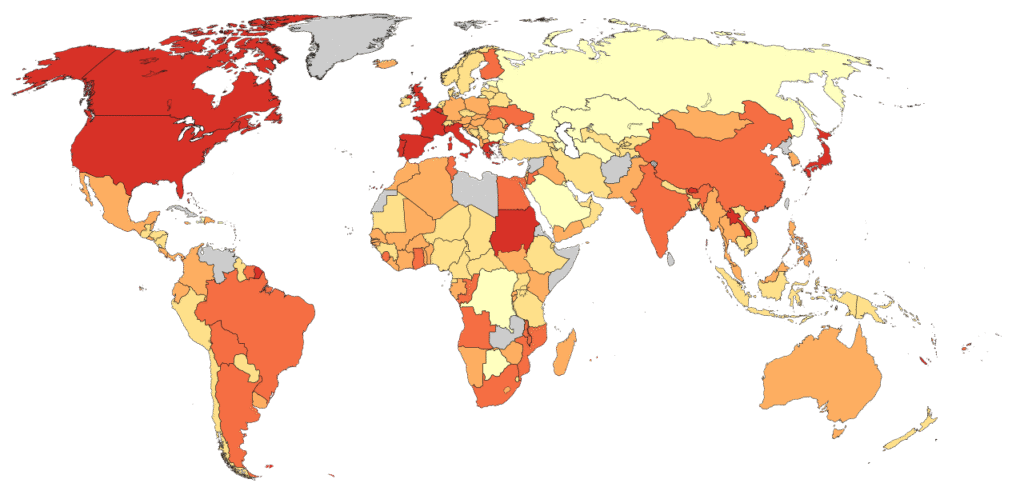

As for the government debt to GDP, the numbers from the same source are 123% for the USA, 250% for Japan, 110% for France, 83% for India, 62% for Costa Rica and 39% for Ethiopia. Below you can see a world map illustrating these levels by range using the 2024 IMF data. The lighter yellow colour is for <25%, pale orange represents the 25-50% range, standard orange is for 50-75%, dark orange for 75-100% and red for ratios above 100%.

Figure 3: Government debt-to-GDP ratio

Credit: Furfur (CC BY-SA 4.0)

Since the global financial crisis of 2008 which required massive government intervention, including the injection of liquidity in the market, and the Covid-induced recession where governments had to step in to keep many businesses alive, the debt level and ratios of governments have been on an upward trend showing no sign of stopping. Furthermore, debt levels in some jurisdictions are misleading as they do not include the debt from non-government entities the government is very likely to bail out if required, whether it is formally guaranteed or not.

It is difficult to see how many of those debt levels are sustainable, only time will tell but things are not looking very good from where we stand today. So, what are the risk governments are faced with and what would the consequences be?

The obvious issue at stake is the continuing ability to service the debt, which requires either the turning of a primary budget surplus larger than the interest service on the debt to permit a partial pay down of the total debt outstanding, and an ability to refinance existing debt by issuing new obligations the proceeds of which are partially or entirely directed towards the retiring of maturing ones. If the investors in the capital markets lose faith in a government’s ability to honour its debt, it will not lend new monies and the government, lacking cash, will default on its debt obligations.

This is not unheard of and if no restructuring agreement is reached then, lacking cash, the government will need to curtail expenses, often cutting down on essential public services or laying off employees in the public sector. Typically, this situation would also lead to capital flight out of the country, see a substantial depreciation of the currency and a spike in inflation, wiping out any savings and purchasing power of the domestic population. This is why countries go at great length not to default and sometimes accept harsh restructuring terms from a multilateral institution such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Such terms almost always include an increase in the tax rate, an expansion of the tax base and a paring down of government expenditures but at least these austerity measures may ensure continuing access to the debt markets and serve as the basis for an economic restructuring and recovery, thus avoiding a total deliquescence.

d) Taxation and welfare

Governments manage a country with different objectives compared to for-profit companies, and these include providing employment, ensuring security, laying and maintaining new roads, etc, but they still need to raise revenues in order to cover expenses. Revenues mainly comes from two sources, the first is the potential profits from any state-owned companies, or the proceeds from their full or partial sale, which is called privatization, and the second is taxation. To clarify, a public service need not always be provided for free, whether it is a road or a hospital for instance, there will be variations in the extent of fees charged to their users and the amount that is effectively subsidized by the government, and this will vary by countries. If a hospital does not charge anything or not much, there is still a cost associated to its operation, whether it is the building maintenance, the purchase of medical equipment and drugs, and of course the salaries of the medical staff. This means that, to balance the budget and avoid a recurring deficit which can be problematic as we have just seen in the previous section, more revenues need to be raised through broader and higher taxation.

Taxes can come in many forms, and one stream of revenues can be taxed several times. The most common types are income tax, capital gain tax, sales or added-value tax, and transaction taxes.

- Income taxes can apply to both corporate and individuals, on their earnings, which for a company would be the net profit before tax line, after having subtracted most charges incurred in the realization of revenues. For corporate tax, the tax rate is often flat, meaning it doesn’t vary depending on the amount of profit though there may be a small tax-free quantum. For personal income tax, a few countries have opted for a low flat rate to streamline the process and make residency there attractive, nonetheless most countries opt for a tiered system with different bands so that the effective or blended tax rate increases in relation with one’s earnings. It should be noted here that some countries provide significant tax advantages for people with dependents in their households, children in particular, while other jurisdictions ignore this aspect.

- Capital gain taxes are a tax on returns from investments. They are based on the difference between the price of a sale and the original price of purchase, sometimes but not always adjusted for inflation, and they require the investor to direct part of the capital gains towards the government coffers. Again, most but not all countries have such taxes.

- Sales taxes are paid on finished products by their users or consumers, they are applied as a flat rate and collected by the seller of the good or services. You would know it as Goods and Services Tax (GST) and a variation of this is the Value-Added Tax (VAT) which works like GST imposed at each step of the value creation rather than only at the level of the end-product. So Company A may purchase raw materials worth 100, transform them in a semi-finished product sold for 150 to Company B and if the VAT is 20%, it will collect VAT on the 150 and claim VAT on 100 so it effectively pays tax on the difference between 150 and 100, which works out to 10. When company B further transforms the semi-finished product and sells it to a consumer for 250, it will collect 20% of VAT on 250 and claim the same rate on 150 so its net VAT contribution is (250-150)x20%=20.

- Transaction taxes go by different names such as stamp duty in the real estate space. They can be a fixed amount or a percentage of the notional amount being transacted, and unlike capital gain taxes, they are not contingent on a profit being realized by the seller; in fact transaction taxes tend to be paid by the buyer while capital gain taxes are of course the responsibility of the entity receiving the proceeds.

As a consequence, taxes are nothing more and nothing less than the stakeholders’ contribution to the state or national budget, and this amount may not bear much relationship with the extent to which this particular stakeholder is using public services. This can be a gripe for many who think they benefit little from all this government expenditures and would prefer to pay less taxes. This might be true, but it may also ignore the luck or insurance aspect: this person may not but could have had a serious accident or disease necessitating major hospitalization or he could have lost his job due to a factory closure or mass lay off and struggled to find a job for a long time afterward. And insurance has a cost because there will be some unlucky people, not everything is within our control.

This brings up the concept of welfare, defined by the Cambridge dictionary as “a system of payments by the government to people who are ill, poor, or have no job”. Again, welfare is not an all-or-nothing state of affairs and there are huge variations worldwide. As it turns out, the issue with welfare is often not the concept itself, it is the excesses and in particular the fact that many individuals, free-riders, take advantage of the system.

With so many sources of taxes, often at very consequential rates, how come most governments incur deficits and see their debt rise to their current uncomfortable levels? The reason has naturally to do with the other side of the budget, the expenditures – there are a lot of them and they do not come cheap. Below is a list of the main categories:

- Armed forces and defence in general. This is expensive in terms of equipment, fuel and payroll. Since we have not reached the end of History as some famously foresaw, this isn’t going away any time soon.

- Legislative and judicial system to pass law and enforce them. A related aspect is policing to ensure order and safety.

- Healthcare, ranging from visits to a general practitioner or a specialist, hospitalization, medication and recovery treatments.

- Public infrastructure in the form of roads, rail tracks, energy generation, water supply and sewage. The price charged to consumers seldom fully covers the actual cost.

- Subsidized public housing, recreation and cultural amenities. The latter two would include theatres, libraries, and sports infrastructure.

- Education, generally starting from a young age all the way to the end of high school. Universities and other types of superior education are treated very differently across countries and even within countries. The main cost here is not so much the buildings or equipment but the faculty payroll.

- Pensions for retirees, allowing them to receive income based on a qualifying number of years of employment and the amount contributed over this period, and unemployment benefits for jobseekers, which tends to be a function of how long they have been unemployed and a minimum duration of work previously.

The latter items are already problematic due to the elevated unemployment levels and the demographic shifts taking place, especially in high-income countries with an ageing population. Ageing on account of the low fecundity rate, which puts a strain on the pensions, especially as the post-WW2 baby boomers are now mostly retired, and because of the increase in life expectancy thanks to the progress in healthcare.

Already challenging and yet, the wave of job displacements resulting from the widespread capabilities and adoption of AI systems is set to catapult this issue at the front of societal issues, not just sink the unemployment benefit system – unless the use of AI systems gets taxed somehow but this seems a hard endeavour in practice. If you want to read more about this topic and other related matters, I invite you to read my essay titled “AI Risks & Mitigations” on the website.

e) Trivia – the allure of gold

We have seen gold mentioned in passing in S6 Section 8.a on the nature and role of money, yet because we did not have knowledge about inflation and sovereign debt at this point, it would have been too early to discuss the role of gold in the monetary system to this day, and today.

When mined, gold can be refined into a commodity with a value depending on its degree of purity, the maximum being 24 carats. It is valuable because it is rare and therefore, while the mass of gold in circulation can increase over time, it doesn’t spike because one entity decides to mint more of it. It spikes when major discoveries are made, or regions invaded as was the case with the Spanish colonies in what is now South and Central Americas. Some of the most famous discoveries triggered the California Gold Rush around 1850s or that of the Klondike in Yukon in the late 1890s.

Originally, gold coins were valued based on their metal content but, as currencies slowly depreciated, this value exceeded their face value and they would be melted. Gold was then used as a fixed reference for many currencies, so that somebody could exchange currency for the precious metal and central banks had to hold enough gold reserves, the same way a bank would need to maintain short term liquidity to honour withdrawal requests from its customers. This gold standard, a key foundation of the Bretton Woods system, came to an end in 1971 and since then we have fiat currency systems. I include a link to the relevant Wikipedia entry in the next section if you wish to know more about this.

One would think that, consequently, gold now trades on the basis of its utility value, either as jewellery or for industrial applications such as electronics. That would probably be the case if there was a wholehearted faith in the current international monetary system, and this is obviously not the case, for reasons exposed earlier in this chapter. This suggests that as long as we can’t turn lead into gold and the supply remains physically limited, this glittering metal is very likely to remain a hedge against inflation, the ultimate hard currency.

f) Further reading (S6C9)

Suggested reads:

- AI Risks & Mitigations essay, by Sylvain Labattu

- Wikipedia on Capital account: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Capital_account

- Wikipedia on Money supply: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Money_supply

- Wikipedia on Bretton Woods: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bretton_Woods_system

Previous Chapter: Money & Banking

Next Chapter: Education & Revolutions