>>> Click here to access this episode of the Syllab Podcast on Spotify <<<

a) Learning through the ages

What a ride it has been, for me definitely and perhaps for you as well dear reader. These Knowledge Series have led us to explore the entire gamut of size and complexity, whether it is the realm of the subatomic or the inconceivably large astronomical phenomena, from simple molecules to complex biological organisms, as well as a wide array of human technological devices and the working of our economy. The main areas I have stirred away from are politics and culture because the dynamics there would require too much time to be spent on genetics so as to make sense of individual drive, as well as on History, because it provides an indispensable context they cannot be abstracted from.

So, my plan for this last chapter in the entire series is to drill home the reason why learning is so important, which is the fundamental reason why they were written, and why education should remain part of a government’s prerogative, as mentioned in the previous chapter, in S6 Section 9.d on taxation and welfare. Before we do that, we will invest a few paragraphs in setting up the context, not by learning about History, but by sketching a quick history of Learning. For once I will use some terms in a very untechnical way so Learning with a capital “L” will refer in turn to various related notions such as the maturing of our ability to think and reason, to the memorization of factual knowledge, and to the development of skills and know-how, which is procedural knowledge.

The etymology of philosophy points to the love of wisdom, thus it encompasses a wide range of disciplines all having to do with the use of reason to make sense of the world, from ethics and metaphysics all the way to biology or mathematics. The father of Western philosophy, from where it is possible to identify an unbroken lineage, at times circuitous and making its way through the medieval Islamic world before heading back to Europe, is undeniably Socrates. He lived during the 5th century BCE in Athens and is known for its trademark epistemological approach, the Socratic method featuring argumentative dialogues. There is no trace or mention of him having authored any text so we are familiar with him, and his celebrated trial during which he is purported to have stated “the unexamined life is not worth living”, through the writings of his equally famous pupil Plato and of Xenophon. Plato is famous for his written dialogues and his theory of forms which is really an enquiry into the nature of reality. They may both have been great thinkers but for a long time the deepest mark was left by one of Plato’s own students, Aristotle, who left a large corpus of integrated knowledge as his legacy – and he also happened to have tutored Alexandre the Great.

So comprehensive was Aristotle’s output, in particular in the natural sciences ranging from the existence of the soul to a universe made of five elements, that it held sway until the Renaissance, partly because it was part of the Church’s dogma, and ideas that would contradict Aristotle’s would end up being discarded even though ultimately none of them ended up being correct. Likewise for the Ptolemaic model of planetary motion. At the time, the main method of learning was scholasticism and it used the Socratic method but always within the framework of the Christian theology. Hence, it took the work of many Islamic scholars and then a few centuries later of Copernicus, Brahe, Kepler and Galileo in quick succession to move away from a geocentric description of the cosmos to a heliocentric one, backed by the improving mathematics and astronomical observations of the time, including the telescope (refer to S3 Section 9.c).

This marked a break with the scholastic tradition and the start of a quest for identifying the cause of physical and biological phenomena, attempting to express these into equations, elegant ones where possible. And so, over time, natural philosophers became scientists and the scientific method based on falsifiable theories and testable hypotheses took off with the likes of Bacon, Descartes and eventually Newton. With the benefit of historical hindsight, the period spanning from the publication of Copernicus’ De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres) up to Netwon’s Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica (The Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy), generally abbreviated as simply The Principia, was termed the Scientific Renaissance and this period was followed by the Age of Enlightenment lasting until the end of the 18th century.

For a theory to be falsifiable it must be able to make predictions and those can then be tested experimentally, and thus the sciences progress through phases of creative destruction, always subjecting their best ideas to the fire, not always so friendly, of enquiry and empirical testing. Unlike mathematics that can provide definitive statements, a theory cannot be proven to be true, and on the contrary it can easily be shown to be inaccurate. So, the theories that become widely accepted are those that have successfully been tested, in the sense that nobody has managed to prove them wrong so far. It is not proof but it increases confidence in the validity of the theory.

Academia, the name given to the research practitioners and faculty of institutions dealing in tertiary education (beyond high school), carries the flame of the scientific method, peer-reviewing publications and ensuring results can be replicated and are statistically significant before they are considered valid and meaningful. However, this is only the sharp end of the education system, the part involved in the creation of new knowledge, but what comes before along a student’s education track is equally indispensable and, in many ways, even more important.

b) The purpose of education

Essentially, what I have just stated is the importance of the education we receive in schools. Here, I am only referring to the academic aspects, not those touching on soft skills, discipline or the drive to study rather than entertain oneself. Not coincidentally, it is compulsory until past our teenage years into most countries on the planet, even if not always enforced strictly, and non-attendance is often the consequence of financial constraints within the household. One often hears that what we learn at school is useless in real life, so why do I take a different stance, acknowledging in passing that the system is far from being ideal.

The importance of academic education has to do with its purpose, which can be broken down into three aspects. Before we dwell into those however, we must step sideways and remind ourselves of the learning process. This was partially detailed in S2 Section 6.d titled “memory, learning and intelligence” and much more comprehensively in Part A of Higher Orders which touches on the nature of concepts, the process of perception, concepts fluidity and analogy, and finally the notion of understanding, before engaging on the topic of consciousness in Part B and that of artificial intelligence and the future of the mind in Part C. Essentially, our mind, which is a handy way to talk about the neurochemistry of our brain, the laying down of memories and the creation or pruning of connections between neural networks, relies on the incremental formation of concepts, the detection of patterns of association and correlation, and the application of different types of reasoning to make sense of the world, accumulate new knowledge and take optimal decisions based on its environment.

Some of these may come naturally, whether they are part of our genetic make-up or the result of observing and replicating what other individuals do, including our parents and siblings, while other aspects can be formalized and taught within institutions through qualified individuals called teachers or professors. So, school provides us with facts to memorize, novel ways to manipulate concepts such as in mathematics or via symbols in the form of a written language, and it imparts to us the rigour required in deductive reasoning. As for inductive reasoning, which is probabilistic in nature and complements the deductive version, our mind unconsciously makes use of it all the time to interpret perceptions but it can also be greatly enhanced through regular stimulation by challenging the veracity of new facts, the logic of some arguments and the reasonableness of intellectual positions. In short, by being a sceptic rather than blindly accepting what we are told or shown. Fostering these skills and attitude towards new information is or ought to be an integral part of the way classes are taught. I include a link to the Wikipedia entry for inductive reasoning in the last section if you wish to get a better handle on this concept and how it differs from deductive reasoning.

All of this is central in developing factual knowledge and practical know-how, qualities indispensable to the economic success of a territory through an increase in productivity, and therefore relative competitive position versus other territories. It is also a key part of children’s education if they are to become responsible and informed citizens.

c) The pillar of sanity

Being a responsible citizen starts with being an informed one and acting reasonably based on the information at our disposal. This doesn’t merely mean exposing oneself to information, it also means using a reliable, trustworthy data set and common-sense reasoning to filter out erroneous data, whether this data was spread with malicious intent of not. It also means not being a willing or unwitting carrier and spreader of misinformation. Of course there is a moral distinction between the two, but not a major one if the unwitting individual has not exercised his societal responsibility of evaluating the truth value of a piece of information and satisfied himself with the soundness of an argument or any other type of statement. Accountability starts with each one of us, and the same logic, the exact same logic, applies to our electoral choices, provided one lives in a system where it is possible to express a point of view.

Exercising our intellectual powers of enquiry and adopting a sceptical approach to information and arguments is not only a civic matter, it is also about protecting oneself and others. Indeed, when not doing so, we can too easily become the victims, directly or indirectly, of individuals or groups seeking their own political or financial benefit, those two dimensions often coalescing. In other words, whenever you display intellectual laziness and do not do your mental homework, you open the door for others to extract value from you, and possibly from all of us.

Not only that, but the sedimentation of falsehoods, over time, is the soil from where alternative History can grow. The term of alternative History here both captures the interpretation of History, and its rewriting. When an autocratic political party in Russia or China does so, the rest of the world can see through it, or at least used to, but now this is no longer systematically the case with international disinformation campaigns and parallel narratives. Furthermore, as far as the domestic audience within these countries is concerned, it is effectively deprived of an objective version of the facts so it is difficult for the population not to buy in the official version, to some degree. This has inspired spin doctors elsewhere and nowadays this systematic denying of facts or their outright invention, the consistent lying, has become a mainstay tool for populist politicians over the world. The reason it has become prevalent is because it works, and the reason it works is because we are not making the intellectual effort to check out the validity of the facts or arguments, or because the truth somehow does not suit our interest or doesn’t align with our beliefs, which is nothing less than intellectual dishonesty.

This rewriting of History isn’t confined to geopolitical aspects or somebody’s actions, it also extends to political systems, as brilliantly satirized in Orwell’s short book Animal Farm, and to economic ones as well, as analysed by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway in The Big Myth: How American Business Taught Us to Loathe Government and Love the Free Market.

The risk, in the medium term, and the process is already clearly visible, is that a large proportion of the electorate and the population at large stops caring about the truth and becomes unable to make the distinction between good and evil, between what is beneficial to Society and what results in value extraction of the many by the few. All this, because we can no longer appreciate expertise and distinguish truths from falsehoods. The alarm bells are ringing but not many seem to care because, in the meanwhile, we are entertaining ourselves.

d) Knowledge is power

Learning and thinking correctly isn’t just a defensive tool, one we ought to deploy to prevent the invasion and spread of misinformation and avoid being exploited. It is also valuable, in particular as the threat of job displacement stemming from the increased capabilities of AI systems has become real. Big Tech and other developers of powerful AI systems claim this risk is over-mediatized and there has been hardly any job losses so far, a statement or argument I disagree with for two reasons: firstly job displacement is not restricted to layoffs, it also encompasses the absence of job creation due to increased productivity, which ends up with a similar result – being one less position for a human, and secondly AI is still in its infancy and we’ll see a step change once proper reasoning models are developed. I have expounded on this position in my essay titled “AI Risks & Mitigations” posted on the website so I will not belabour the point here.

It did not take the Information Age to realize that knowledge is power, the aphorism was first written in Leviathan by Thomas Hobbes who heard it from Bacon: “scientia est potential”. It is power both because of the information aspect, knowing something that others don’t, but perhaps more importantly because of one’s ability to arrive at a correct position and, if one follows the path of rationality in her actions and behaviours, to live a more principled and fulfilling life, in adequation with the rest of her environment. Likewise, mental fortitude backed by thoughtful analysis and decisions, allow one to resist the pull of the herd and do what is right, anywhere, all the time. Here I am of course using a very loose concept of knowledge, one that extends to reasoning faculties and other intellectual skills, not just the storage of data in memory.

In a way, it is fitting that this most abstract and perhaps most complex aspect of our biology would be the one on which evolutionary pressure is making itself felt. Not that this should come as a surprise since for a few millennia already, the most blatant change in our physical appearance compared to our cousins the great apes has been the fine-tuning of our motor control and the increase in the size of our brains, including the development of the pre-frontal cortex which reins in our primal, reflexive behaviours and emotions. We have not become bigger or stronger, we have become more intellectual and technical, giving us the ability to understand and manipulate the world around us.

e) Reaching the summit

The cynic would ask if we would not be better off going back to a pre-technological society, one with less stress and worries about what the future may bring. The answer is that the unruly law of the jungle would be all but stress-free and we would need to worry very much about tomorrow, every single day. The path to the simple life is not one where we give up everything but one were we distance ourselves from our more basic needs and stop creating new ones. Undoubtedly, we should cater to our physiological and safety requirements but we should strive to cease feeling their gravity upon our shoulders, the unrelenting want for more food, goods and pleasure.

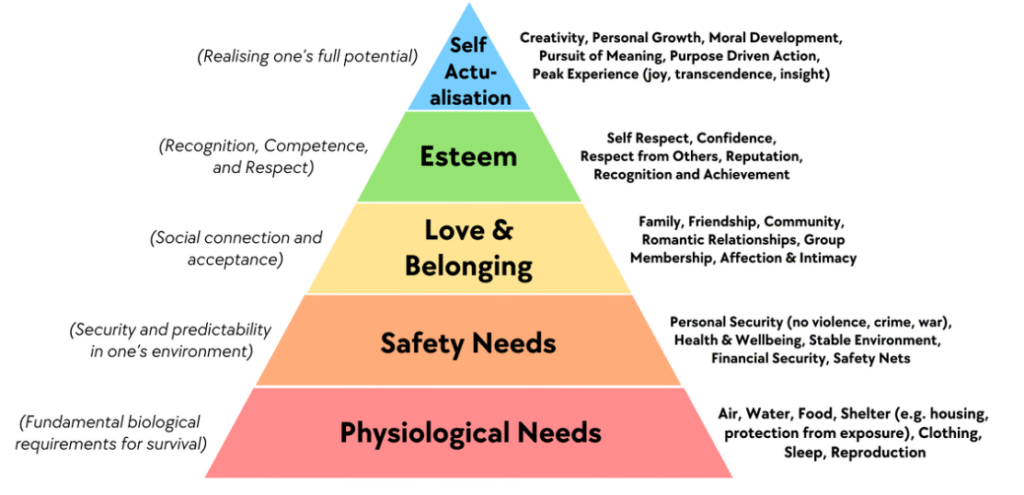

This looks very much like the Buddhist equivalent of renunciation and detachment, and why not? But what does it have to do with knowledge or education? Simply, that such a step is necessary though not a sufficient one and, in order to grow and fulfil our own potential, we need to progress towards more abstract goals and mindsets, starting with caring for the people around us, respecting our own self, before progressing to the final stage, the pursuit of meaning or “self-actualization”. This reflects the well-known hierarchy of needs from the psychologist Maslow, often illustrated as a pyramid, a version of which is enclosed in Figure 4 below, though that was not a metaphor he used himself.

Figure 4: Interpretation of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs

Credit: Hamish.crocker (CC BY-SA 4.0)

In his words, “what a man can be, he must be”. This is the meaning of self-actualization and the reaching of such state requires knowledge, including that of our own body, the way genes and our environment drive our behaviour, in order to detach ourselves from those chemical forces and decide who to become, what to do, and why. It also necessitates the ability to think through the right from the wrong, the good from the evil, not because they exist but because those notions must be created in each person’s mind and serve as our compass if we are to make our way to the top.

This is it and, following the custom of the last day of class, I release you early though not before one last trivia. Closing two loops at once.

f) Trivia – the Trivium

The word trivial means something is of little consequence and therefore trivia is a piece of information with little value. Something that is nice to know but not particularly useful. In Latin, trivia is the plural of trivium, and initially it referred to “three roads” (via means road or way ) but during the European Middle Ages it came to refer to three of the liberal arts: grammar, rhetoric and logic.

These three were called the trivium and taught first before things got serious with the other four liberal arts, the quadrivium, encompassing arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music. Thus, of the educational corpus, the trivium was considered comparatively easier and perhaps less consequential than the quadrivium. By analogy, and exaggeration, this gave us the term of trivial.

f) Further reading (S6C10)

Suggested reads:

- The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, by Thomas Kuhn (buy)

- Higher Orders, by Sylvain Labattu (buy)

- Animal Farm, by George Orwell (buy)

- The Big Myth, by Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway (buy)

- Wikipedia on Inductive reasoning: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inductive_reasoning

Previous Chapter: Sovereign Economics